Years ago, when keeping the scorecard for a team was the job of the second, it was quite possible for a relative novice to end up being responsible for noting scores, and that could be quite an uncomfortable experience, on top of trying to bowl properly. These days, with the skip assumed to be keeping the card as well as keeping the scoreboard right, it is clearly more likely to be an experienced player wielding the pen. (As we shall see, that doesn’t mean there are no errors!)

However, it is quite likely that a club member will be asked to mark a singles game. Last year I remember a District singles competition where there not enough markers and various spectators or supporters were roped in to keep the card, and needed to be told how to do it – not something to inspire confidence either for them or for the players. There are various official statements about the role and duties of the marker, dealing with things like keeping still, or limiting speech to factual statements rather than advice, but not a lot about the actual card. This post will look in a little detail at the mechanics of keeping the score – and the same points will apply whether it is in singles or part of a team performance.

Whatever shape the scorecard is, or whatever extra writing it has, the basic point is that all cards comprise two halves, one for each team/player, and each of these columns is sub-divided into two – the first showing shots scored on each end and the second giving the cumulative total. If you already feel insulted at this statement of the obvious, please bear with me and try to remember that the sight of such a card can reduce a new bowler to total panic.

When playing in a team it is quite easy to keep a check because there is another skip standing alongside, and the two skips also have to deal with the scoreboard. This doesn’t mean there are no slippages, but it does underline the importance of keeping in touch. Just last week I heard of an outlandish situation that occurred in a league match involving my previous club back in the UK. It was a game where three rinks each played 21 ends, with the overall result based on rinks and shots won. As it was getting dark, two rinks came to the end of their game, but the third had a dispute because one skip thought they had finished while the other said they had played only 19. How on earth that could happen, I don’t know. The fact that two other rinks had finished must suggest that unless there was some ridiculous slowness, the third should be finishing too. But on the night, much to the annoyance of those waiting to get home, it was decided to play two more ends. Viewing this from another continent, it seems highly likely that that rink in fact played two extra ends. Fortunately it affected neither the result on that rink nor the overall score, but one can imagine that had the shots margin swung in favour of the side wanting to play on, the atmoshpere would have changed!

So let’s turn to the more mundane issues of writing a single-digit number and then adding it to another number almost certainly less than 30… As noted earlier, this is not just a question of mathematical ability. Other things can happen to distract the card-keeper. I would certainly admit to having almost lost track of scores, both as a skip and as the marker in a singles game, and while the sense of panic that can ensue is not exactly up there in nightmare territory it does feel very awkward and embarrassing, and likely to leave you flustered. It isn’t good to be hastily calculating that “it must be an even number of ends because they are bowling in this direction” or trying to remember whether the score three ends ago was a one or a two.

The routine which seems safest is to note down immediately, and at the very least, the number of shots for the winning player/team. Because the score for the other side is by definition zero, that detail could – if necessary – be filled in later. But as long as the actual number of shots on each end is noted as a first step, the other three columns in each row can be calculated and inserted as soon as possible, if not there and then. For instance, you (as the marker) are at the head as the players eventually decide it is 3 shots to player A. You need now to get to the other end of the green ready for the next end. So note down 3 for A, and you can fill in the other parts of the row while the first bowl of the next end is being played. Nothing you do (card, scoreboard, putting away a measure) should hold up the players as they want to get on with the next end. they have their own rhythm, and the marker shouldn’t interfere with that.

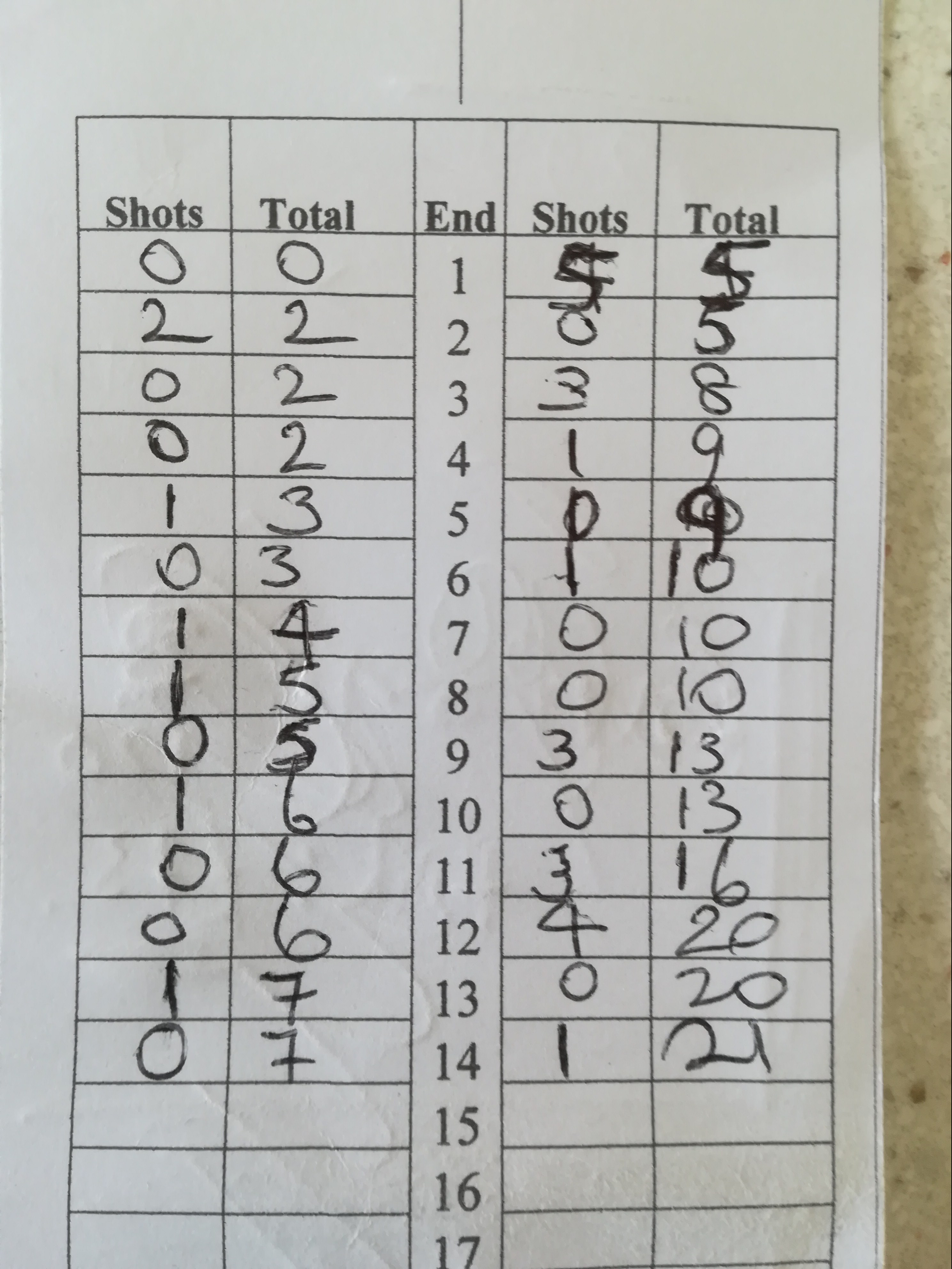

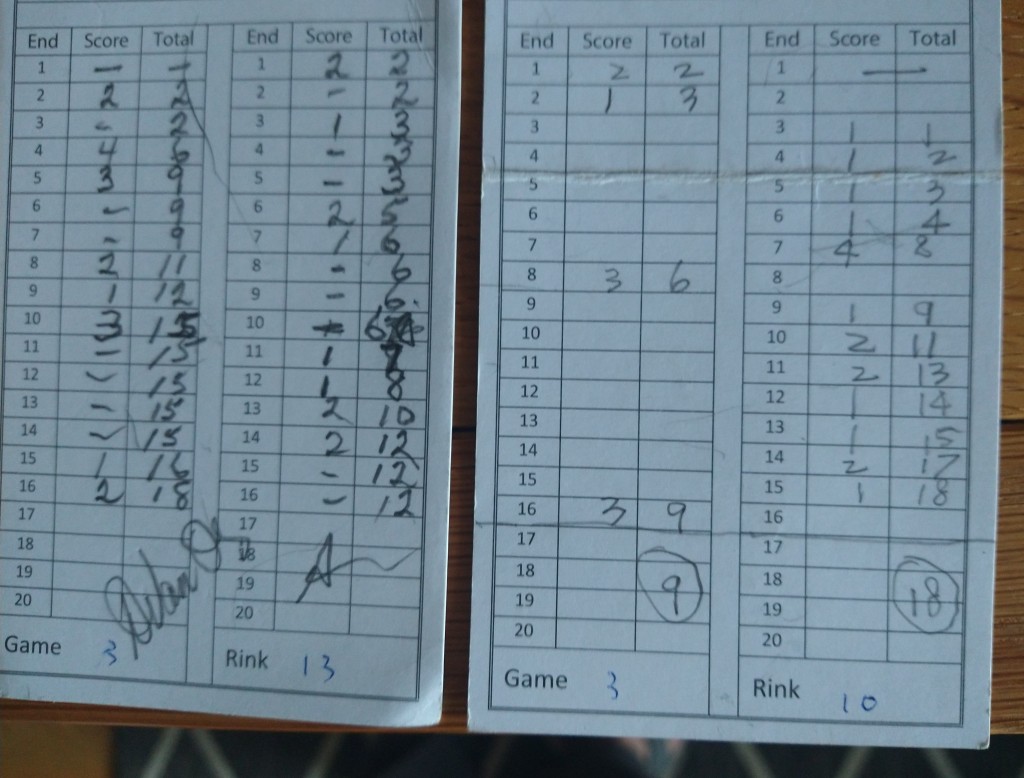

These two cards were taken from a collection of old tournament cards at our club – filled in by unknown competitors from a variety of clubs. They are not unclear, and as cards go they are pretty good. But if you look closely you will see that one error was made on each. On the first one, the error was immediately seen and corrected: on the second end, a 2 was added to 1 to give… well, something other than 3, anyway. This was then overwritten in time for the other ends to be right. On the second card, the identical box (second end for the team on the left) has a more subtle error. You can see that a zero was recorded for a lost end, but this was then followed by a zero for the cumulative total, which of course should have been 3. Fortunately this error didn’t work its way down the card, as a six on the third end restored the total score to nine. But it could easily have become much more confusing, with debates between the skips about what the score should be, and you really don’t want that in the middle of a game.

When looking out examples of real cards to use in this post I came across several examples of cards where only the winning ends were recorded. Now it is possible that this is a widespread habit, but I have to say I have never come across it before. It so happens that the example below is about the neatest one of all the images given here, but I would still advise against it. My reason is that having only one line filled in removes an important crosscheck when comparing scores between themselves and with the scoreboard. It sounds like a recipe for the sort of confusion I mentioned at the start of the article, with someone “out” by two ends. Aiming for an empty line rather than the next line clearly has more chance of error. And it’s not enough to say that the chance of error is not very great – it doesn’t matter what the competition is, it’s the most important one in the world for the people playing!

You may also notice here that the card on the left had an error on the tenth end. I would imagine that this shows that the score was filled in some time after that end, because if it was done as soon as the score was decided the skip could hardly have confused three shots for his team (the corrected score) with one shot to the other team!

The card on the left also brings in the question of how to record zero scores on each end. There is no objective answer as to whether an actual zero (0) is better than a dash (-) to signify a lost end. But since this is a personal blog I’ll give my personal view that a zero is better, simply because there is just a chance that a dash could be read as a one (1) if it were tilted at all from the horizontal (I’ve seen it happen). You may argue that a zero could be mistaken for a 6 – fair point, but on the balance of probabilities I would still say a “0” is safer. Let’s say a player starts with four blank ends. When she does get on the board with a single, the difference between 0 and 1 is so very obvious, and much clearer than having yet another single pen-stroke. There is another small advantage of the zero. When you come to recording the (admittedy very rare) “no shot” end where neither side scores, it can be indicated by having dashes or even a solid line through the row to show that although no shots were scored the end does count; the difference from other ends, where only one side scored zero each time, will be very obvious.

Whatever you think of the individual bits of advice given here, just develop a routine and a rhythm for noting the scores, and (in a team game) checking them against the board and the other card (“Ten-six after 12?”). If you are marking singles, especially if you don’t know the players, it will help if you add words to their names (“red bowls”, etc). It’s also useful to keep the names on the scorecard in the same position as the names on the scoreboard. I admit that all this is marginal, but – just like bowls itself! – small margins can make a big difference.